Will AI Kill Teamwork?

What the fall of bands can teach us about the economics of teams in the age of AI.

I’m experimenting with AI to translate my posts. Check out “Will AI Kill Teamwork” in: العربية | Português | Bahasa Indonesia | 简体中文 | हिन्दी | Français | Español.

TL;DR.

Technology and incentives reshaped the music industry. Solo artists replaced bands because they were cheaper, able to produce faster, and easier to manage. This shift eliminated the creative friction that once defined much of music's richness. A similar dynamic may now be unfolding in knowledge work. AI reduces the cost of solo production, making teams less attractive unless they consistently outperform in quality. If expectations of quality decline over time, the economic case for collaboration may weaken, and we may not realize what we have lost.

Bands are Disappearing

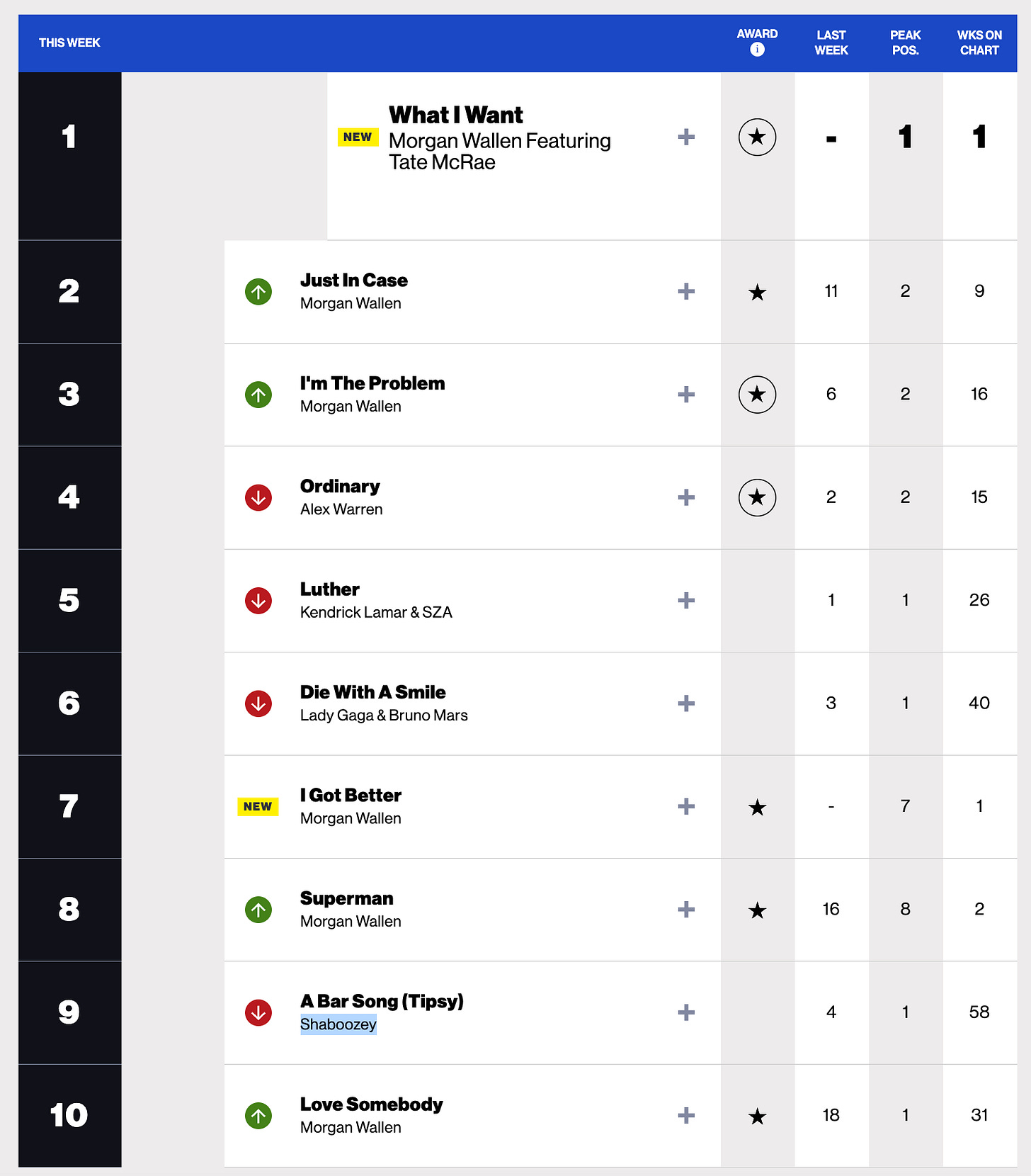

I recently watched a YouTube video by Rick Beato, in which he made an interesting observation: there are almost no bands on the charts.

There are lots of solo artists. But very few bands.

What are bands? Bands are teams of people bringing together their skills, often as equals, to create music. I've been thinking a lot about his observations about bands over the last few weeks. Are we witnessing something similar in the world of knowledge work because of AI?

Bands Were Once Ubiquitous and So Were Fans

When I was a kid, all I listened to were bands, old and new: Led Zeppelin, The Doors, Radiohead, Soundgarden, Rage Against the Machine, and later, Massive Attack.

My first concert was Rage Against the Machine at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City in 1996 (I was 15). After school, I walked for two hours from my house in North Brunswick to Cheap Thrills, a record store in New Brunswick, New Jersey, to buy tickets.

A few months later, I went to see Soundgarden and saw a band member (maybe Chris Cornell?) storm off stage. Then, a few months later, Soundgarden broke up for good.

This friction, as explosive as it was, is what made bands, well, bands. Each person brought something distinctive. The music was an outcome of a superadditive function.

So, why have bands disappeared?

The Economics That Made Bands Disappear

According to Beato and others, the disappearance is caused by a mix of two forces: technology and incentives.

It’s useful to sketch out the band story and explore how far this analogy helps us understand the ways AI and incentives may weaken teamwork in other industries.

Success in Music is Power-Law Distributed

Music is meant to evoke a feeling. If it creates a desired feeling (happiness, hope, inspiration, even anger), people desire more of it and are willing to pay for it.

“Willingness to pay” (WTP) can be seen as the value generated by a piece of music.

Yet, even with very high WTP, the prices of records, CDs, and even streaming subscriptions remain relatively fixed. At a $15 price point, you get widely varying types of music with differing willingness to pay.

What drives profitability in this industry, then, is quantity.

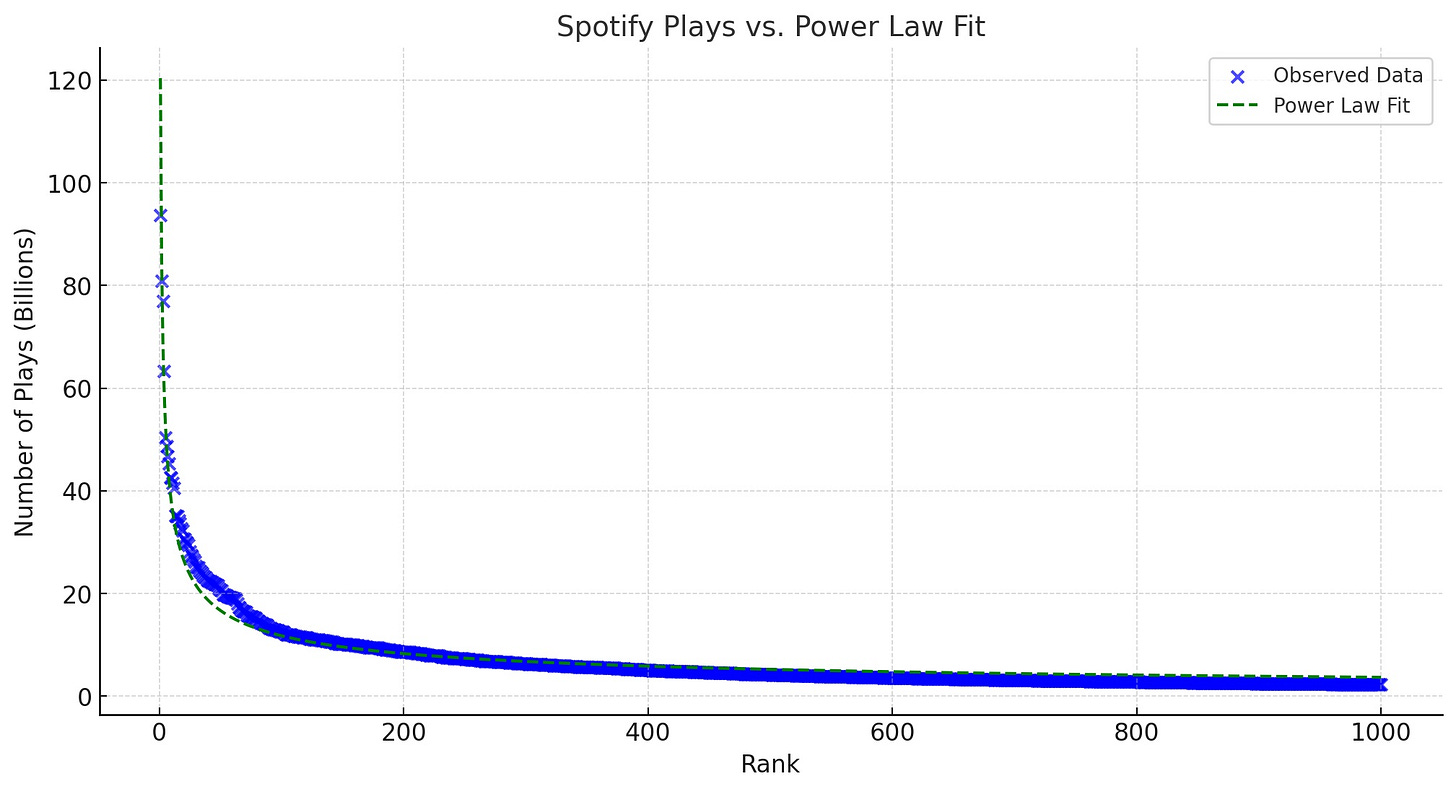

The problem with music, as with many creative goods, is that willingness to pay (or success) is not normally distributed. It's very skewed. This is called a “power-law” distribution. Most artists get few listens. But a tiny fraction explodes.

Consider the number of streams on Spotify. It is a power law distribution. A few artists get most of the listens, and most get very little.

You Need Multiple Shots on Goal to Win

Given this distribution of success, a record company can only profit if it achieves a few mega-hits since, statistically, most artists tend to fizzle out. (This is not all that different from venture capital, book publishing, academic papers, tweets, apps, and consumer products)

This is further complicated because, ex-ante, you don’t know whether an artist is going to be a hit. That is, on average, it’s hard to pick winners. It depends on a lot of interacting factors. And thus is susceptible to a weakest link problem (e.g., x1 * x2 * x3… xn), and if any x is missing, you get a dud.1

How Do You Cut Costs in Music?

With power-law distributions, you need multiple attempts to succeed. In most cases, the results are “0.” Sometimes, when luck is on your side, you achieve the extreme outcome necessary to recoup your investments. The economics of streaming also reinforce the payoffs for massive hit singles.

A label’s incentive in this environment is to have as many shots on goal as possible. If they have a hard budget constraint, say K, they will try to squeeze in as many artists, with some cost c, as possible in that budget. This means that you need to have very low c per artist to buy enough lottery tickets to get a hit.

What should the label do? It should cut out expenses and figure out a way to spread costs across many different bands. To do this, they could:

Hire a songwriter who composes for multiple artists rather than commissioning custom songs for each project.

Use a drum machine instead of hiring a live drummer.

Replace natural, organic instrument recordings with high-quality synthetic or virtual instruments.

Smooth out the voice of a bad singer with a pretty face with Autotune

In fact, the solo artists themselves can do much of this in their bedroom with an Apple MacBook Air. They can sing someone else's song (or their own, if it is any good) and tell the computer to generate drum sounds, guitar, and bass. The computer will comply.2

It is not hard to see that the cost of a solo artist c(s) is substantially lower than the cost of a band c(b).

In addition to input costs, you also reduce the “interaction cost.” If the solo artist is in full control (they tell the computer music software precisely what to play) or the music is purely the vision of the producer, there won't be any conflict between team members, shortening production cycles.

The music then becomes the linear vision of the artist. No pushback.

And, indeed, this is what we've gotten: Hozier, Ed Sheeran, Sabrina Carpenter: economically viable, built for scale, and low creative friction.

Compare this to 1980, where nearly 50% of the top 10 are teams.

Losing Creative Friction

The economic system of music doesn’t favor bands. And it seems that the incentives were ALWAYS this way.

So what changed?

To produce music, you needed bands because you did not have viable sonic substitutes. Today we do, so the outcome has changed.

We get fewer bands.

Do Teams Create Different Music Than Solo Artists?

When teammates are replaced by technology, something else also disappears.

Most individuals have a sense of self and a desire to assert their vision on the world.

Individuals will resist the undue influence of others. They will push back. This friction can be both constructive and destructive.

In music, this creative tension has served as a wellspring of tremendous sound.

Two examples come to mind.

The Police are notorious for the friction between Stewart Copeland and Sting. In fact, there are several YouTube videos showing Sting and Copeland arguing with each other (here and here, though sometimes in jest). In a fantastic interview with Beato, Copeland notes that Sting's willingness to push for his vision developed after many of his songs became hits. It was a belief in himself that allowed him to advocate for his ideas within the band, The Police.

Copeland, considered one of the greatest drummers of all time, did not want to be merely an arm of Sting’s vision and, of course, pushed back. This friction led to sometimes dysfunctional interactions among team members, but also to incredibly sublime music.

Listen to Spirits in the Material World. Every instrument and every sound is intentional. You can tell that each sound is coming from someone who cares, someone who owns what they're producing, someone who wants their voice, their sound, to be heard. First, focus on the drums only. Then the bass. Each person is making the music theirs. Go back and listen to Hozier, Sheeran, or Carpenter, and you can hear the difference.

Listening to them is like squinting, but with your ears.

Another example of creative friction is Mezzanine by Massive Attack. It is perhaps one of the greatest albums ever recorded. A genre-defining work.

It also led to the “breakup” of Massive Attack due to creative differences between Robert Del Naja (in front) and Mushroom (Andrew Vowles, in the middle).

In an interview around the time of the release of this album, Del Naja talks about how creative friction is necessary for breakthroughs to happen. Mushroom, sitting in the middle, looks upset.

“There is always tension in music. Sometimes it’s a good thing, sometimes it’s a bad thing. When it is a strong creative process and we all feel strongly about what we are doing, we’re gonna come up against each other, you know. Quite heavily sometimes, you know. And there is going to be a lot of aggravation, but that’s just the way we’ve always been….It’s part of it, really, part of the process.”

After Mezzanine, Massive Attack was no longer a band. The “band” was a project mainly of Del Naja and his musical vision. Not that I'm the most sophisticated listener of music, but nothing matches their earlier albums as a band: Blue Lines, when their vision aligned, and Mezzanine, a powerful work of creative friction.

At their best, bands aren’t merely linear collections of skills; they are multiplicative production functions brimming with conflict and energy in ways no single person can replicate.

Will Artificial Intelligence Kill Teamwork?

I believe we can learn a great deal from the music industry about how incentives and technology, particularly AI, will impact teamwork in knowledge-intensive industries.

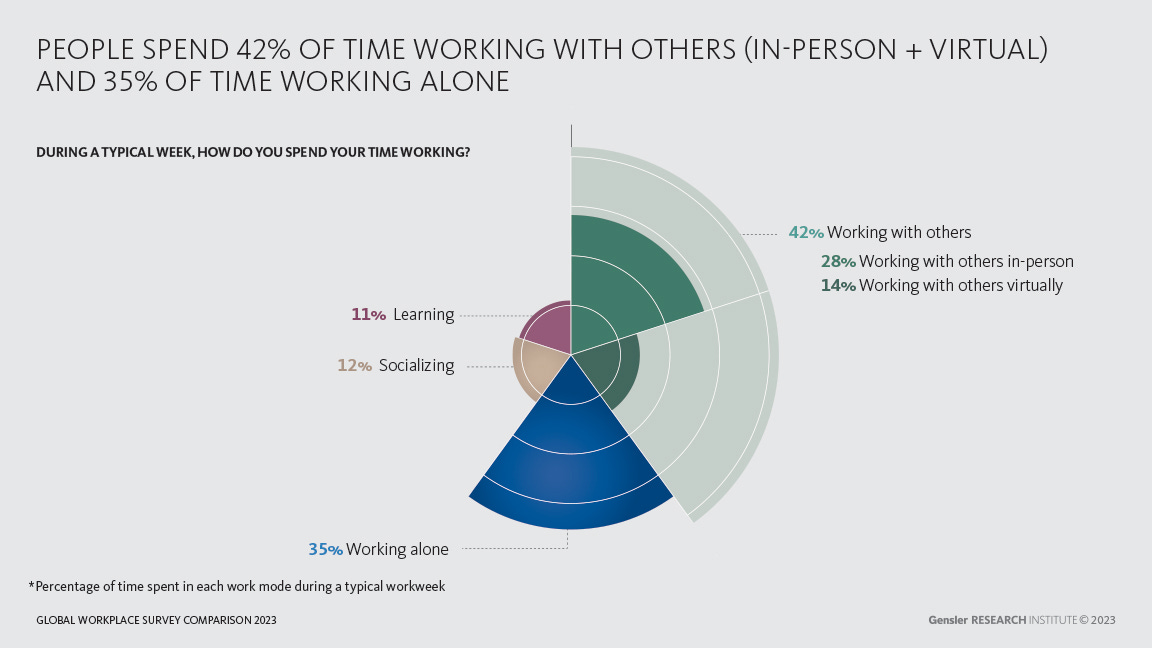

Teamwork makes up a large fraction of people’s time

“Team” work makes up a substantial proportion of how people spend their time at work. A recent survey found that knowledge workers spend 42% of their time collaborating with others (more than solo time, 35%). I imagine if the question were something like: “What percentage of your time contributes to team-level outputs?” the number would be larger.

The big question for me is: How will AI affect collaborative knowledge work?

Team Types and The Impact Of AI

I think this likely depends on what problems teams exist to solve.

In terms of production:

Type A teams are teams where most people can do most jobs. But teams exist for three purposes: (a) scale, since one person doesn’t have the time to do everything so they delegate; (b) flexibility, since there is variability in who is available to do work, when; (c) learning, because teams are designed to develop the next generation of talent.

Type B teams are teams of specialists where each person owns a distinct, non‑overlapping skill set. The team exists for three purposes: (a) depth, because no individual can master every niche; (b) coordination, because clear ownership reduces handoff errors; (c) innovation, specialists can bring in advances that a generalist doing the same thing can’t. (There is a version of Type B teams with similar skills, but different “perspectives.”)

Type C teams are teams where people enjoy working with each other, independent of functional reasons.

These are not pure types but rather points on a spectrum. Academic research in the social sciences aligns more closely with Type A (most researchers are taught to do everything, e.g., write, model, analyze data, etc.); physician teams in complex cases tend toward Type B (anesthesiologists, surgeons, etc.), and Type C teams are distributed throughout.

I believe AI currently poses the greatest threat to Type A teams. As models improve, AI may also threaten Type B teams (though I’m less sure when this will happen, given the current weaknesses and strengths of foundation models).

I hope Type C teams will remain unaffected by AI's influence. However, I’m not sure. Many people are using AI for companionship and support.

How AI is Affecting My Teamwork

When I think of my own research teams, they are mostly Type A teams (with some members having relative strengths but not deep specialization). While they have remained the same size so far, AI has already had profound effects:

Low‑level tasks (data cleaning, literature searches, grammar edits) are primarily handled by AI (custom scripts; ChatGPT, Grammarly). This has freed up time to think at a higher level about other problems.

My best PhD students have extremely strong AI‑usage skills: prompt crafting, troubleshooting AI output, coding, and verifying accuracy independently. They are also extremely smart in various other dimensions.

I’ve found that my PhD students have become substantially more autonomous; they solve roadblocks (e.g., structuring data, thinking through empirics, finding relevant literature, etc.) using AI rather than escalating to me.

Overall, I focus a lot more on “structuring” and strategic choices rather than nitty-gritty stuff, while each team member can execute autonomously with far fewer bottlenecks.

Because so much of the lower-level work is made easier, we are spending a lot more time on the big picture.

At some point, it is not hard to imagine turning this patchwork AI team into an integrated and autonomous research team. Perhaps this team may be more auditable than a human team.3

Will AI Replace the Band: Rethinking Collaboration in Knowledge Work

The big question is whether this shift on the supply side will lead to the same dynamics we saw in the music industry—e.g., toward solo creators substituting teammates with technology?

If we think about it from a demand‐side perspective, solo individuals > teams when at least a few things are true:

Hits are unpredictable ex ante;

The market’s payoff for a “hit” is convex;

There are strong Matthew effects (success begets success).

So, when do teams survive?

I think it boils down to the following:

Teams have a higher probability of getting a hit than solo artists, and this is known ex ante

Consistency matters more than extremes

The payoff from the increased likelihood of success overcomes the higher cost of the team.

In other words, if you know a team can consistently meet the quality threshold often enough (even at a higher cost), then its “hits-per-dollar” outperforms a solo+AI lottery ticket. However, if uncertainty is extremely high, payoffs are heavily skewed, and solo+AI costs are so low that you’d prefer to take more inexpensive shots, then teams become less viable.

We May Not Notice What We've Lost

On the demand side, if quality thresholds are fixed and set outside our control (e.g., exogenously), teams will survive only when their combined expertise raises the chance of meeting that bar enough to justify higher costs.

In that case, it is a simple economic calculation: if a team’s output clears the standard far more often than a solo creator with AI, then paying for a team makes sense.

If a solo creator can hit the same mark almost as frequently but at a fraction of the cost, then the team option loses out.

The Danger of Lowering Our Expectations

But everything changes if quality thresholds are shaped by what the audience comes to expect or by relative comparisons.

What if our expectations of “good” or even “amazing” are lowered through some social process (e.g., grade inflation)? In this case, gradually, we might settle for whatever solo + AI can deliver.

The bar moves downward to match cheaper, AI‑driven work, and teams lose their clear advantage.

Even if a team could produce something objectively better, no one would value (or even know how to assess) that higher level if expectations have already fallen. Once quality standards become endogenous and trend downward, there is no economic rationale left to pay the premium for collaboration.

In other words, even economically viable teams endure only so long as the market insists on a higher standard.

When we lower our standards, we may not like what we get.

The scarier thing is that we might not even notice.

Let me not end on a sad note. One antidote to this downward spiral is to develop our taste for the beautiful things that are still out there. These are the pieces of superadditive magic we find in music, sports, science, and at work, too.

These awe-inspiring things may be harder to come by, but they do still exist. We have to notice them, appreciate them, and realize that they may take a bit of conflict to make.

Another possible economic factor influencing the lack of diversity in mainstream music today could be the economics of streaming. In the past, physical album sales represented a one-time transaction that encouraged artists and labels to produce unique content to stand out. However, with streaming, the focus appears to favor repeat listens over distinctiveness. It seems that the most successful tracks are those that listeners can enjoy repeatedly, which may lead to a preference for safe, familiar, and predictable music. This might shift the incentive towards conformity rather than innovation or genre exploration, as artists potentially feel pressured to align with already successful sounds in the streaming landscape.

If the artist blows up independently, say on TikTok or YouTube, then they have negotiating power with the label.

The other thing to consider is that the current AI teammate is a generalist. As a generalist, it's probably not very good at the particular tasks that it does. An 808 machine is not going to produce drumming like Keith Moon, Stewart Copeland, or John Bonham (and of course, on tabla, Zakir Hussain). So, a lot of drums across many albums will sound mostly the same.

Made me think about Uzzi and Spiro-- teams are not just multiple groups of people, but people embody mixtures of previous teams that they have been a part of.

Even if AI reduces the creative frictions within teams (or reduces most creative activity to solo+AI) it might have a net positive effect by amplifying "scenius" (scene genius) dynamics or how communities lead to phenomenal output. This might be especially true as AI amplifies exchange of tools and techniques so that scene members can more quickly remix and build on each other's innovations.

If you haven't come across the term, here's Kevin Kelly's overview of scenius: https://kk.org/thetechnium/scenius-or-comm/