The Gifts of New Jersey

The Zen of America's Most Misunderstood State

TL;DR

New Jersey played a leading role in inventing modernity, but it never built a mythology around it, while Silicon Valley can't stop telling its story. This reveals an interesting pattern: innovation hubs rise through specialized advantages, only to become traps that prevent adaptation. But New Jersey discovered something profound by accident. In moving beyond its achievements and simply existing without needing to prove anything, it found its authentic self.

Growing Up Without a Story

I grew up in New Jersey.

I never really thought much of it. I went to high school in Central Jersey and then college at Rutgers in New Brunswick, just a few minutes from where I grew up.

In many ways, New Jersey was an ideal place to grow up. It was culturally diverse, bustling, and living close to New York and Philadelphia gave anyone who wanted it world-class global exposure to arts and culture. Moreover, New Jersey was a place where successive new waves of immigrant communities came, worked hard, generation after generation, and achieved the American dream.

But New Jersey also had this gritty cultural element that was completely authentic and incredibly endearing. One of my favorites: Fat cat sandwiches at the grease trucks at Rutgers (sandwiches with cheese sticks, two hamburgers, fries, all loaded on a giant bun). At one time, a version of this innovative caloric monstrosity was named the best sandwich in America.

Fat cat sandwiches represent this live-in-the-present existence that typifies New Jersey for me.

Moreover, characterizations of New Jersey “life” with the success of The Sopranos and the controversial show Jersey Shore (whose cast was a bunch of New Yorkers!) ostensibly gave people a “window” into Jersey life that just reinforced the gritty aspects of its culture. And of course, who can ignore The Boss.

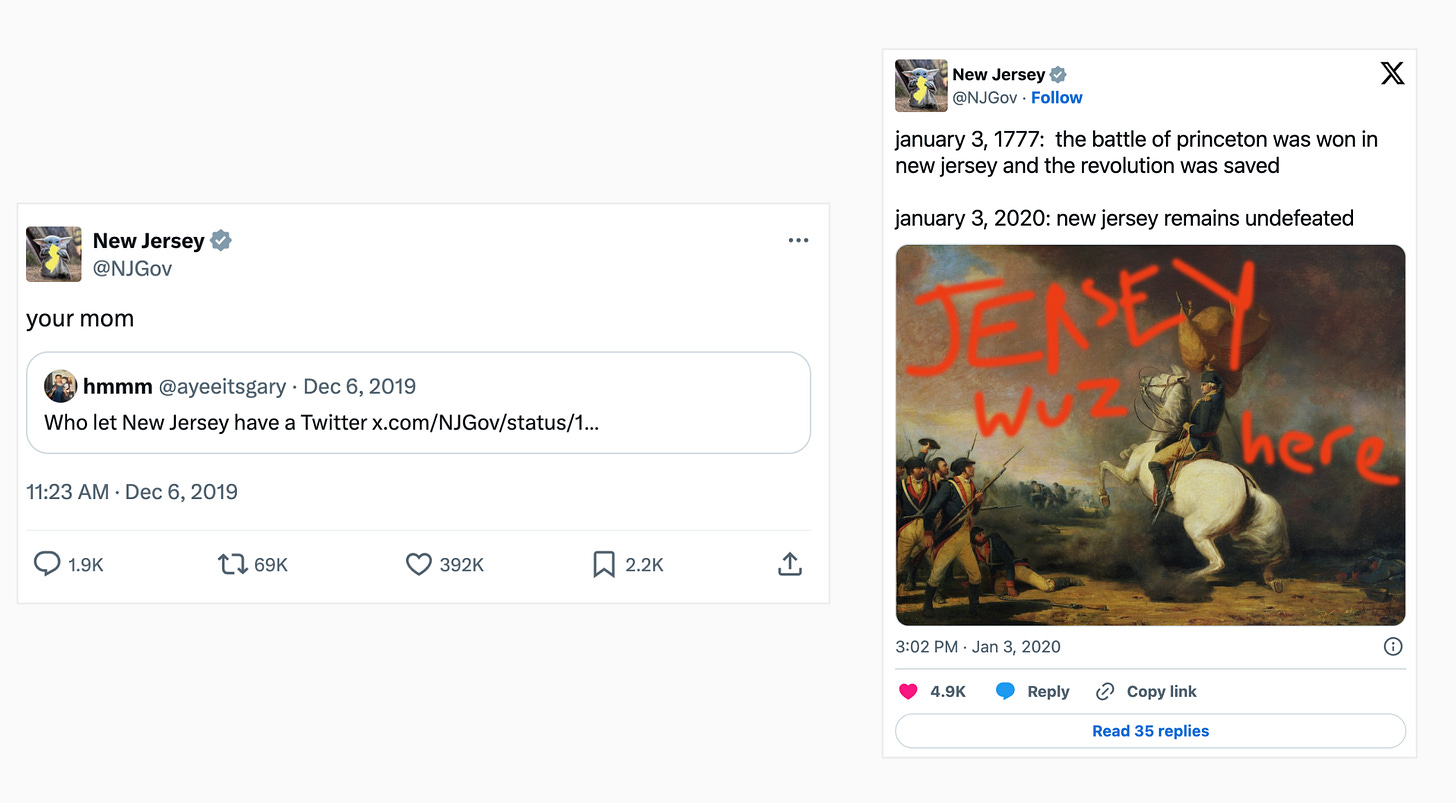

What I especially loved about New Jersey was that people didn’t sugarcoat anything. It was real. New Jersey is tough, fun, authentic, and unfiltered. And the state has leaned into this idea of itself. Even the official New Jersey Twitter account picks fights with Delaware and casually responds to tweets with “your mom” and “JERSEY wuz here.”

Midway through college, though, I was ready to get out. The whole scene wasn't for me: wearing all black clothes from the Banana Republic outlet and clubbing every Friday; then heading back on Monday to some back-office IT job at a finance company in New York. None of it seemed appealing.

I felt like opportunity wasn't going to meet me in New Jersey. I got into graduate school at Rutgers (but also in New York and Philly), but decided to take a chance and leave for Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon.

Chasing Lost Glory in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh was radically different from Central New Jersey, and Carnegie Mellon embodied much of this cultural energy.

You could feel the hunger: greatness had been lost and needed to be reclaimed.

Pittsburgh was fighting hard to reinvent itself, determined to become the most inventive region in America. You could see the transformation happening: buildings in Oakland were being scrubbed clean with decades of smog finally coming off.

Pittsburgh also had a wealth of amenities from its past as one of the world’s great industrial hubs: museums, concert halls, mansions, the Steelers (they were in the Super Bowl three times when I was there; they won twice), and most of all, its people’s fighting spirit.

But what I loved was that Pittsburgh kept its authenticity, the same quality I appreciated about New Jersey.

Here is a promo video from Carnegie Mellon, “Today we work.” Telling the story of the creative working-class ethic driving the university and the city.

San Francisco Bay Area and the Myth Machine

Six years later, I moved to Stanford, California. In the San Francisco Bay Area, history was still in the process of being made. Silicon Valley was really only 50 years old by this time.

I arrived in 2010, just as the tech rebound from the financial crisis was getting underway. There was this constant buzz, but it wasn't about where the Revolutionary War was won—it was about where the Future would be won, where tomorrow was being invented.

California had this unshakeable self-confidence that it was the cradle of America's tomorrow.

Stanford was at the epicenter of this myth-making.

California has built a near-complete mythology around itself and tells these stories really well. It gets others to tell these stories too (I’ve done my share of this, too).

Do you have a dream?

Got a garage?

You, too, can create the future and become a billionaire.

The Research Triangle’s Clean Slate

Then we moved to the Research Triangle area of North Carolina.

The Research Triangle is also a place in the making, but it's different. Unlike Pittsburgh, it doesn't lean on its past. Unlike New Jersey, it isn't gritty. And unlike California, it's not buzzing with the kind of energy and ideas that come from everyone feeling like they're building a rocket ship (or have a lottery ticket in their pocket).

North Carolina wants to move beyond its past (it was once a slaveholding state). The Research Triangle, in particular, is a place where you go to start fresh with your new house, your corporate job at a respectable company, and your high-quality of life.

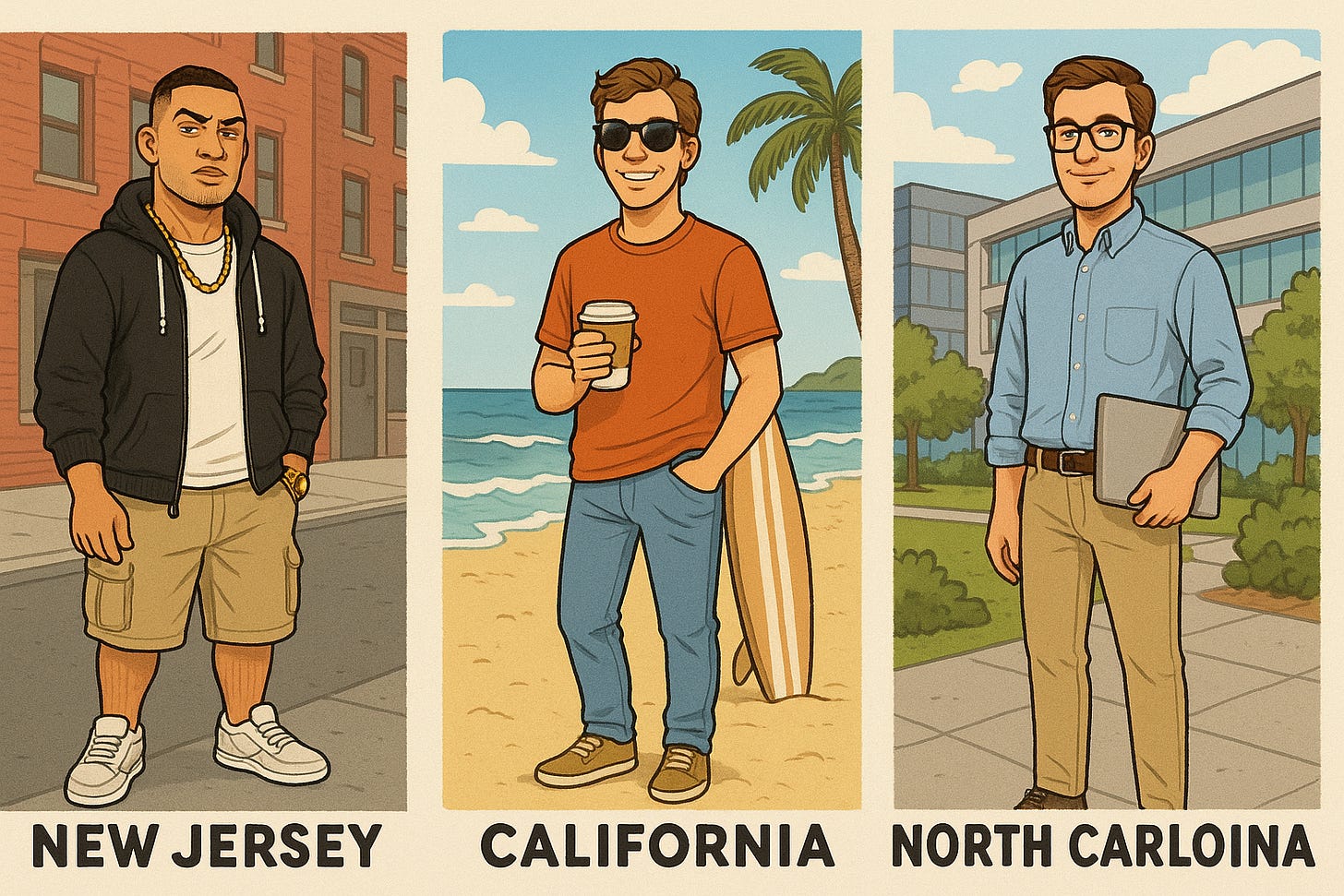

If you think these are just my stereotypes, here's a ChatGPT-generated image with a simple prompt: "Generate an image of what you believe the typical person from New Jersey, California, and the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina looks like."

These cultural types and stories told about them are so pervasive that this is now embedded in the billions of parameters of modern LLMs. Digital stereotypes.1

A few years ago, driving down Route 1 in New Jersey past the strip malls and the old Regal Cinema where I worked, then to Route 130 past my high school, I realized something.

I lived in New Jersey until I was 23, but New Jersey never really told me its story.

Jersey was just there.

Meanwhile, California wouldn't shut up about Silicon Valley, and Pittsburgh and North Carolina were busy trying to elbow themselves into the spotlight by “reinventing” themselves.

But New Jersey? It never talked about what it actually built. Nobody mentioned that before Silicon Valley was even a dream, New Jersey was inventing the modern world.

When Jersey Invented Tomorrow

Robert Gordon's The Rise and Fall of American Growth makes a very interesting observation: that the rate of American economic growth has been in decline for some time. In particular, there was a special century between 1870 and 1970 in which some of the most important technological breakthroughs in human history happened. After the 1970s, growth slowed.

During this truly transformative period, we gained the foundational technologies: electricity and the lightbulb, the internal combustion engine and automobile, powered flight, running water and indoor plumbing, air conditioning, communication systems for voice and data across vast distances, and the semiconductor and transistor enabling the digital age. Similarly, the chemical industry gave us plastics and synthetic materials (think everything you’re using today, including the clothes you are wearing), while antibiotics and modern vaccines revolutionized medicine.

Our physical landscape also changed: our cities were reshaped by skyscrapers, subways, and elevators.

This was the invention of modernity itself.

New Jersey played a starring role in this transformation.

The state was central to the global technological revolution from the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution.

Starting Up New Jersey’s Innovation Era: The Late 1800s

The gifts of New Jersey are perhaps too voluminous to mention in the context of a blog post. Several researchers have written about this in various forms, and there's always a list floating around once in a while in a local New Jersey newspaper about all the great inventions coming out of New Jersey.

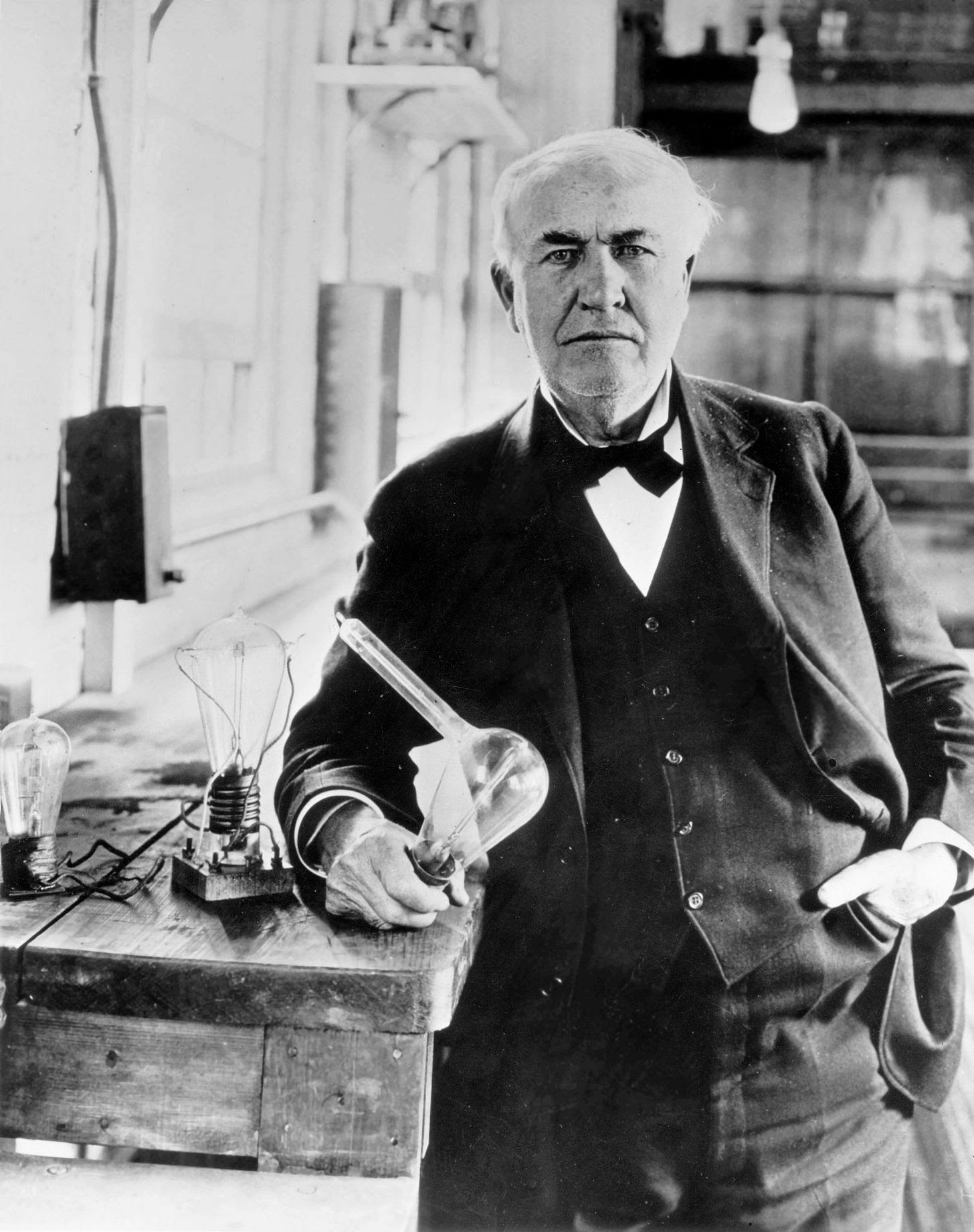

Perhaps the most important of all of New Jersey's institutions for innovation was Thomas Edison and his industrial research laboratory in Menlo Park. This was Menlo Park, New Jersey, rather than California.

Edison's invention factory produced a series of breakthrough technologies during the late 1800s. From the phonograph in 1877, which allowed for the mass production of sound, to the carbon microphone for telephone transmitters in 1877, the most powerful of these inventions was perhaps the development of a practical incandescent light bulb in 1879. Edison tested thousands of filaments in a trial-and-error process (that he would repeat to solve other problems) to figure out how to create a light bulb that would be economically and practically viable. This one invention alone shifted humankind's relationship between night and day, transforming life as we know it.

Even foreign companies such as the Marconi Company, based in the United Kingdom, incorporated its US entity, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, in 1899 in New Jersey. The first station in America was located in New Brunswick.

Creating Modernity in the Early 1900s

By the Early 1900s, it was more than just Edison who was making breakthroughs in his New Jersey laboratory. Brothers Robert Wood Johnson, James Johnson, and Edward Johnson founded Johnson & Johnson in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 1886. Johnson & Johnson, known for consumer healthcare products today, developed a set of breakthroughs that would transform surgery, including the first industrial sterilization process, the Band-Aid, and the first maternity kit. These breakthroughs revolutionized medicine, preventing the deaths of perhaps millions of individuals due to infections caused during surgery or even minor scrapes. Johnson & Johnson, in response to the 1918 flu pandemic, invented and then distributed a mask that would help prevent the spread of the flu.

It was more than just technology and medicine where New Jersey excelled. Joseph Campbell founded Campbell's Soup Company in Camden, New Jersey. Campbell's hired John T. Dorrance, who was a chemist with degrees from MIT and Germany, to develop a process for condensing soup, as the heaviest ingredient was water. What's interesting about this scientist-turned-businessman, Dorrance, is that he eventually ended up buying Campbell Soup and turned the business into one of the greatest American brands ever.

Post World War II and the Digital Revolution

If all of this sounds impressive, there was more to come.

Post World War II, New Jersey was to become one of the greatest fountains of innovation in human history. In particular, AT&T's Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey, was to become one of the epicenters of the digital age.

One of my favorite books for a general audience on innovation is “The Idea Factory.” Many have written about Bell Laboratories in one way or another as a fountain of innovation driven by large corporate labs staffed with brilliant basic scientists, from physicists to chemists to mathematicians, and engineers, who would solve both long-range and short-term problems for the monopolistic American Telephone and Telegraph.

Bell Labs was responsible for a dizzying number of inventions, from the transistor to the Telstar satellite communication system, to the Unix operating system, the first mobile phone, and major advancements in fiber optics. In addition to these breakthroughs in hardware, there were conceptual breakthroughs too that happened in New Jersey, including Claude Shannon's development of information theory, which he began at MIT but developed further at Bell Labs.

Post World War II, New Jersey was also the scene of major pharmaceutical breakthroughs, including the development of Valium in 1963, which skyrocketed Hoffmann-La Roche to become one of the major pharmaceutical giants.

New Jersey was a powerhouse beyond just corporate research. Two of New Jersey's major universities, Princeton and Rutgers, were hotbeds of innovation in their own way. The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, an independent research institute at one point headed by Robert Oppenheimer and staffed by people such as Albert Einstein, proved crucial to global technological progress. Princeton University housed John von Neumann, who pioneered computer architecture and game theory, Alan Turing during his foundational work in computer science, and John Nash with his Nobel Prize-winning work in mathematics and economics. At Rutgers there was Selman Waksman, who discovered streptomycin (a major treatment for TB) and won the Nobel Prize, along with key advances in ceramics, pharmaceuticals, and environmental science. The Institute for Advanced Study hosted Einstein, Oppenheimer, Kurt Gödel, and Freeman Dyson.

But now, when you think of innovation, you think of California rather than New Jersey. What happened?

Why wasn’t Silicon Valley in New Jersey?

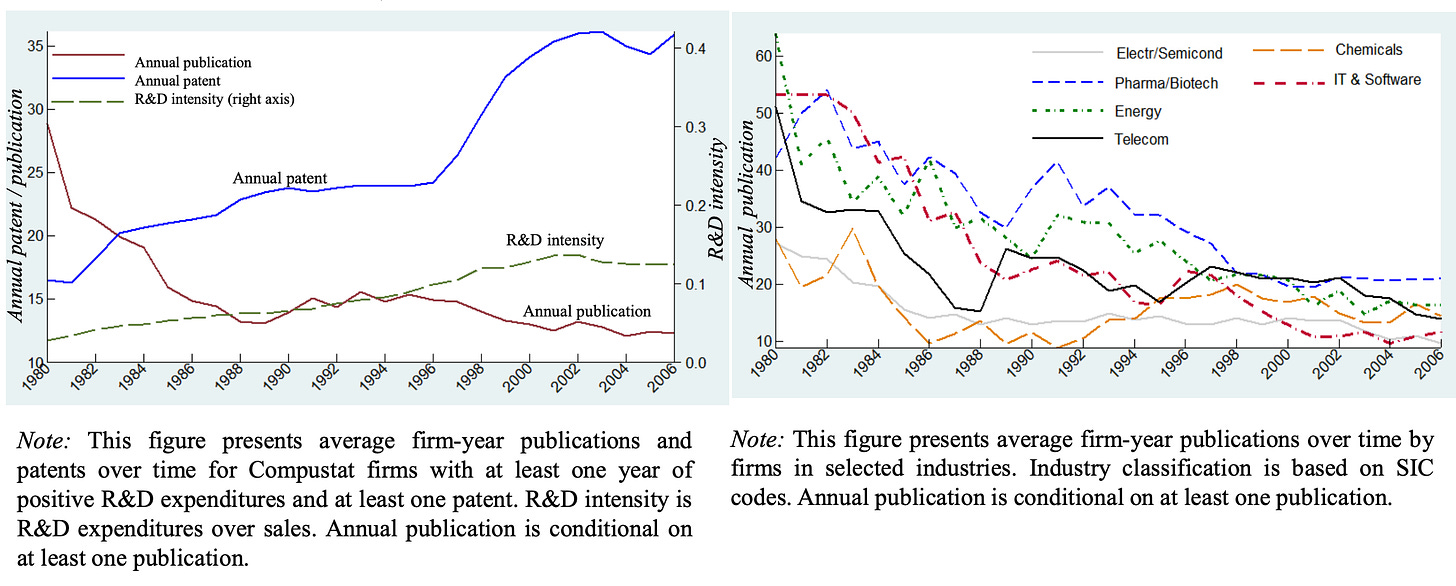

My colleagues Ashish Arora, Sharon Belenzon, and their co-author Andrea Patacconi document that starting about the same time Gordon identifies as the end of the special century, from 1870 to 1970, you began to see a pretty drastic decline in the production of basic academic publications by corporations. I've discussed this before in a different post, but the decline of science in corporations was a pretty significant moment in the history of innovation.

But it also hints at what happened to New Jersey.

Despite the fact that some of the world's most advanced corporate research laboratories, Bell Labs, RCA, and Roche, were based in New Jersey, the ecosystem that generated breakthrough innovations appeared to falter.

Little by little, New Jersey's edge in the innovation game was being lost.

What California Did Right

At the same time, California was beginning to build an ecosystem in its own right. As always, the fundamental input to any innovation ecosystem is talented men and women, both individually brilliant and collectively spectacular.

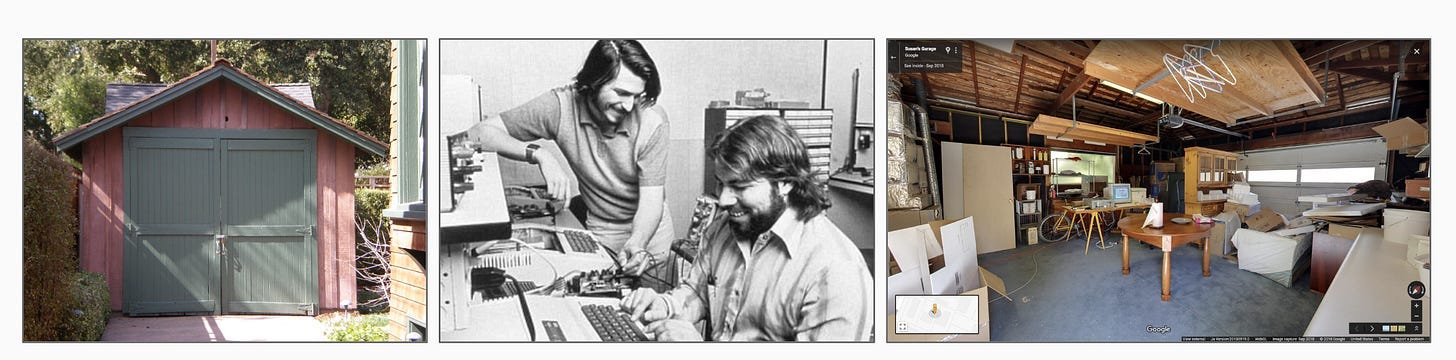

Perhaps one of the founding stories of Silicon Valley is the movement of William Shockley from Bell Labs in New Jersey to Palo Alto, California, where he became a professor at Stanford University.

As I've written before, Stanford at this time was being led by Frederick Terman, who was slowly transforming the university from an intellectual backwater to one of the greatest universities in human history.

Shockley's intemperate behaviors, the self-confidence of the young scientists working for him, and a chance encounter with Arthur Rock led to the creation of Silicon Valley: startups, first Fairchild Semiconductor, then Intel, and the financing mechanism of venture capital. This replaced the need for the deep pockets of large corporations to fund long-term basic science aimed at maintaining monopoly power, with clear blessings from the federal government and the restrictions that came with it.

Several factors drove this shift from a corporate research model to a disaggregated startup ecosystem: a steady flow of motivated individuals graduating from universities in California and a consistent migration of people moving west from New York and New Jersey. Changes in capital markets and various other developments, such as Stanford's creation of the technology park on its campus to enable students to start companies using technologies developed in university labs, also contributed.

One of the most notable failures of the corporate research model for me was Xerox PARC. Xerox, a traditional East Coast company, established a research center in Palo Alto. PARC was an innovative and brilliant place, and several books have been written about it, including one of my favorites: “Dealers of Lightning.” PARC was where the graphical user interface, Ethernet, laser printing, and the mouse were developed. However, Xerox and its management, often called the “toner heads,” only focused on their existing markets and allowed Silicon Valley startups to take these ideas and develop them further. As a result, both Apple and Microsoft implemented many of Xerox’s innovations in their own products.

The new ecosystem, built with these various complementary components, was able to turn ambition, intelligence, and money into businesses and ideas that reached product markets faster than any slow-moving old corporation back in New Jersey.

Once these complementary institutions reached a critical mass, Silicon Valley was more than just a collection of startups; it was a complex set of interconnected institutions with significant feedback loops (see Saxenian’s Regional Advantage). A startup, for instance, generates returns for its founders and investors while also training the next generation of founders who now have built connections with each other and can source both money and human capital.

The Great Brain Drain

By the 1980s, the narrative around Silicon Valley had itself become a powerful competitive edge.

Every day, the Silicon Valley chronicles keep being written: about how young people with their brains, ambition, and the support of an ecosystem could make a mark on the world.

It began with Hewlett and Packard in a garage; then the Traitorous Eight broke away from Shockley to create Fairchild Semiconductor and later Intel, the startup of startups; then the next wave of startups came with Apple, Sun Microsystems, and then Google; and now the AI boom is here, based on the same fundamental story: Go West.

New Jersey as America’s Education Factory

What happened to New Jersey?

It could hardly compete with Silicon Valley; how could anyone?

Despite this transformation, New Jersey is not just another has-been backwater: it remains a vibrant, growing state. It remains #1 in terms of population density, #11 in total population, #3 in per capita income, and numerous other rankings.

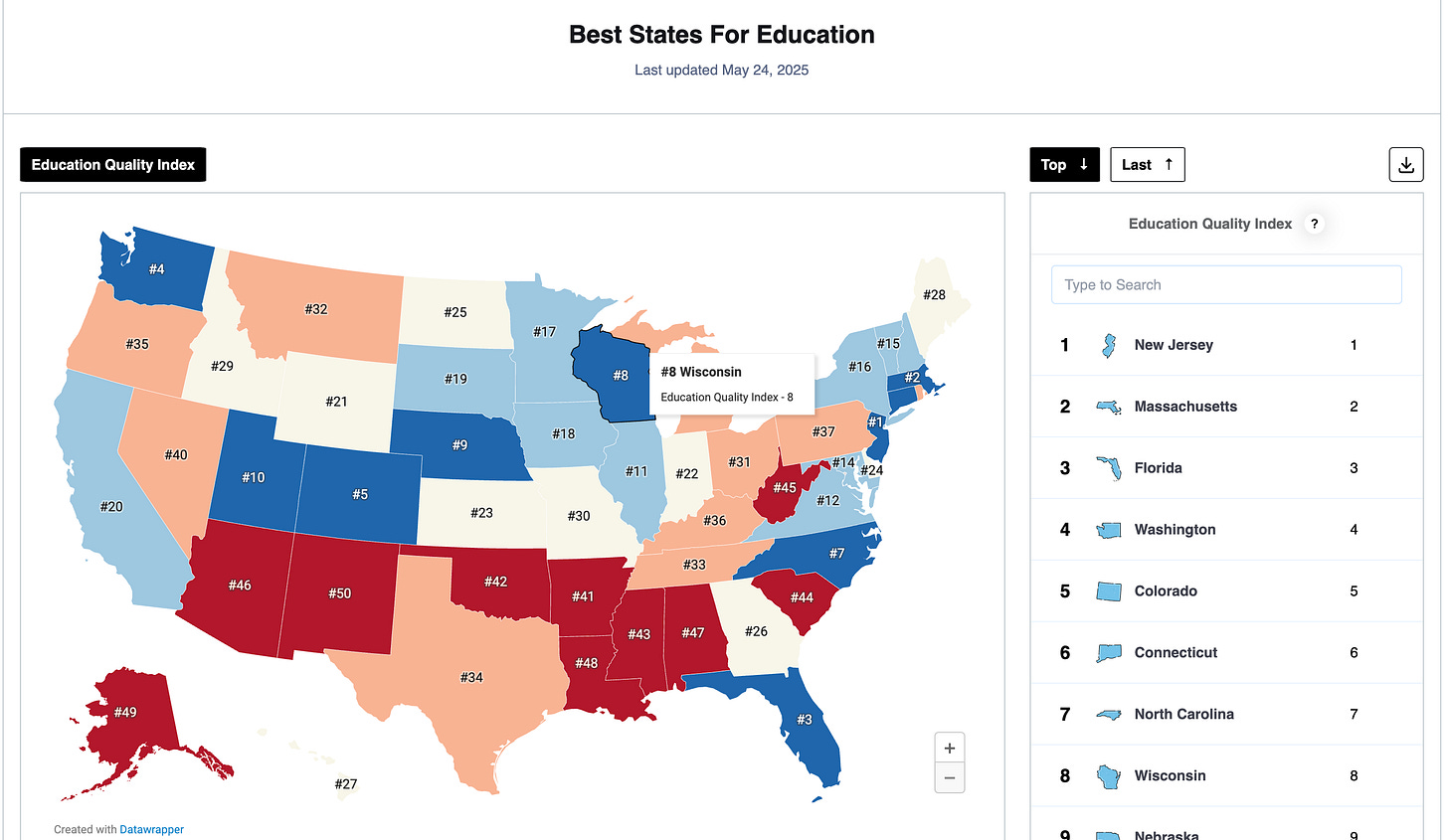

But most importantly, New Jersey remains one of the best places in the entire country to get an education. The state consistently ranks at or near the top in many educational rankings. US News & World Report ranks it number one in the nation. Another website (datapadas.org), which gathers data from various sources, also ranks New Jersey number one, followed by Massachusetts and then Florida.

California, on the other hand, isn’t really doing that great in this regard.

What's striking about New Jersey is that statistics suggest a large percentage, somewhere between 30 and 50%, of New Jersey's high school students attend college out of state. There are excellent options for bright students from New Jersey, both in neighboring states, with New York hosting several Ivies, Connecticut having another, Pennsylvania offering some great universities, along with Maryland, and even further south here at Duke University.

New Jersey is a net exporter of human capital. There's a brain drain going on.

In contrast, very few outsiders come to New Jersey for college each year. The main attraction is probably Princeton University, which is less of a local New Jersey college (even though it used to be called The College of New Jersey) than an international institution.

New Jersey's talent exodus seems like a sad coda to the disappearance of its innovation economy over the past half-century.

The Costs and Benefits of New Jersey

Having left the state, right after receiving my excellent and affordable public university education, I understand the economic calculus that causes people to leave.

People leave New Jersey for many reasons. I've highlighted some of the factors on the “benefits” side of the equation. New Jersey seems to lack the opportunity of other states when it comes to the frontier of the economy: technology, innovation, and even finance. Those things are happening in California, Boston, and New York.

But there's another side to this equation as well: costs. New Jersey is also a very expensive place to live. Property taxes are among the highest in the country. State taxes are also high. It's difficult for young people to put down roots.

In this way, North Carolina had significant advantages for quite some time (though it is also getting expensive here). It was a place where you could leave New Jersey, stay in the same time zone, enjoy better weather, and maintain an affordable middle-class lifestyle with a solid middle-class job.

California, though the situation was somewhat different, still offered significant benefits, even though the costs were also high (a typical house in Silicon Valley now costs well over $1 million). So if that cost-benefit balance works for you, it could be an excellent place to live. If you’re ambitious, it's worth considering. However, you need to understand that California has an up-or-out economy. There’s little room for the normal person with a regular job.

The Rise and Fall of Innovation Economies

But the rise and fall of regions is more than just a story of New Jersey. It appears to be a recurring pattern in economic geography that suggests something more fundamental about the rise and decline of innovation ecosystems worldwide.

We've seen these stories before. For example, the rise and subsequent fall of Manchester's textile industry. Manchester dominated global textile production for over a century. It had remarkable competitive advantages and specialized infrastructure, both economic and technical. It seemed like it would be the textile capital of the world forever.

But soon, competition arrived in the form of America. Cheap cotton from the American South shifted production away from Manchester to the United States, and then farther afield, eventually reaching Asia. Manchester's population peaked in the 1930s at 766,311 during the interwar period and dropped to nearly half that by 2001, with 392,819 residents. Today, the population of Manchester has grown again, but it is Manchester in name only. It is a different city with different people and different industries.

This appears to be a universal pattern—the cycle of birth, death, and reincarnation of major innovation hubs across different regions. We saw this in Detroit, where the population dropped from a peak of 1.8 million to 600,000 today, in Pittsburgh, and later in New Jersey. These cycles also trace back even further to the rise and fall of other important regional economies: Rome, Greece, and the Indus Valley civilization.

This pattern and its samsara-like rhythm are instructive and, in some ways, a predictable outcome of the forces of efficiency and the inertia that result from developing a well-oiled economic machine with complementary assets that are highly specific to a particular purpose. Specialized infrastructure, tacit knowledge, dense networks of suppliers and talent—all optimized for producing a specific type of value—drive these complementarities, which generate increasing returns, fostering a virtuous cycle and competitive advantage.

But this optimization can become a trap that may be hard to escape.

And once the game is set, an equilibrium emerges. We may start to see the gaming begin, which always happens when a place shifts from primarily creating value to extracting value.

Soon, new places emerge that have figured out how to generate more value using a completely new system of value creation. People, money, and other resources start going where the action is.

Then the cycle repeats.

“Just Being” New Jersey

As the cycle makes another rotation, maybe New Jersey has discovered something profound.

While Silicon Valley relentlessly pursues the next unicorn, Pittsburgh grinds to reclaim its storied history, and North Carolina tries to win the next corporate back office, New Jersey has achieved something special: the liberation that comes from having nothing to prove.

New Jersey gave the world the light bulb, the transistor, and satellites.

And now it seems completely content with the fact that you don’t know this.

I’ve started to rethink the fat cat sandwich from Rutgers' grease trucks. The fat cat is the embodiment of “just being”: excessive, authentic, and couldn't care less about what you think.

What I learned from living in New Jersey is perhaps that not every place needs to be an innovation hub chasing agglomeration and increasing returns. To many, New Jersey's lost glory and its outflow of human capital may be viewed as a tragedy.

However, it may actually be New Jersey's way of giving back to America, not through a flashy app that goes viral, but through the human capital (and the attitude that comes with it) that makes it possible.

The endless cycle of regional rise and fall, as seen in Manchester, Detroit, and possibly Silicon Valley next, hints that trying to stay permanently relevant is like trying to hold water. The more regions squeeze, the faster they lose their advantage. New Jersey seems to have learned this by chance: by loosening its grip, it discovered an unexpected balance.

In my mind, New Jersey exists in an eternal present, neither mourning too hard for the past nor reaching too far for the future, simply doing what needs to be done.

Maybe New Jersey's greatest gift wasn’t the transistor, the light bulb, or its many students who go elsewhere.

Its gift might be the understanding that a place doesn’t need to prove anything to matter; it can simply exist.

ChatGPT really needs to work on its defaults around who it generates.

Great post, Sharique! Really enjoyed the read and the think. Who tells the stories of these places and shapes the narratives? I can’t shake the feeling that the root goes deeper than general vibes about what sorts of stories to tell. Not a ding against your narrative, just a question about how such a decentralized process arrives at such different outcomes….

This is a most rich, informative, and satisfying post! I rarely feel so compelled to read a post multiple times, feeling pressed for time and always in need of better time management skills so I can get "more" done where more too often means a higher pile of outcomes that will strengthen or sustain a story I think I need. "The Gifts of New Jersey" illuminates the dysfunction of this state of mind for me in surprisingly direct fashion. The lovely thing about being is that it is THE default condition. Cultivating meaning and purpose around that seems time well spent. Perhaps the ultimate takeaway for me, even with all the powerful and entertaining history and evidence you've masterfully infused this piece with, is just a simple reminder: "At my best, I'm me."

And you had me at Grease Trucks.