What Just Hit Us?

Technological Change and the Rise of Structural Sociology

"Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther... And one fine morning—So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past." - F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

Several weeks ago, my daughter wanted to watch The Great Gatsby (she eventually read the book too). I hadn’t thought about Gatsby since at least high school, and even then, I didn’t fully understand it. In my mind, it played like a Bollywood movie: boy loves girl, girl loves boy, social class keeps them apart… Even the fact that Amitabh Bachchan was in the remake we watched aligned with my notion.

But now I see it: Gatsby was a mirror.

His story reflected his society. Gatsby strove to transcend his humble beginnings through relentless reinvention, through his dress, his speech, his affectations, and his wealth. It’s as if he drank the Power Pose Kool-Aid.

But in the end, the real power belonged to Tom Buchanan, whose dominant position in the social structure made him secure. Gatsby, in contrast, could never grasp the green light. Real power was forever out of his reach.

And what was this social structure that gave Buchanan so much power?

Buchanan’s power felt effortless and absolute because of a web of institutions, connections, social capital, class, wealth, and cultural legitimacy.

Gatsby was a mere status hack. In the end, the social structure caught up with him. He was shot dead in his pool, blamed for a crime he didn’t commit, while the Buchanans walked away untouched.

I once asked my advisor, Shelby Stewman, what the phrase “social structure” actually meant.

We were crossing Forbes Avenue in Pittsburgh after class. He looked down the street and said, “You don’t see a truck here, do you? Then, suddenly, it comes outta nowhere—at full speed—bam, it hits you. And you don’t even get to ask what the **** just happened. That’s social structure.”

Gatsby never saw the truck coming.

But social structures don’t just magically appear. They are built, shaped, and reinforced by larger forces, and few forces shaped the world more profoundly than the rise of global trade.

Trade and the Global Economy

If the Age of Exploration has a starting point, it is often traced to 1415, with the Portuguese conquest of Ceuta. Almost immediately after, many European nations began expanding sea routes and connecting to different parts of the world.

By 1492, Columbus arrived in the Americas. Then a few years later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India. Spices, textiles, and humans, both free and enslaved, moved across continents.

Wherever there was demand, new ventures arose to create supply.

This expansion in trade also led to important institutional changes. New organizational forms emerged, most notably the rise of joint-stock companies that allowed strangers to pool capital. New institutional arrangements, such as limited liability, were also introduced, enabling people to invest in risky ventures without risking total personal loss. Alongside these came the legal and financial infrastructure of capitalism: property rights, contracts, corporate charters, and formalization of double entry accounting in 1494 and its eventual use by companies to grow into sprawling and complex organizations (a great book on the rise of accounting is Jacob Soll’s book, the Reckoning). With these innovations and increasingly better knowledge of trade routes and navigation, capital could now create and capture value across an expanding global trade network.

By the 1800s, the basic institutional skeleton of modern capitalism was in place. Global markets, financial infrastructure, and institutions protecting capital had emerged—alongside new social structures.

New classes, as writers including Marx noted, were increasingly self-aware of their growing wealth and influence. They sought to protect and preserve their position in this emerging global order.

However, while trade had dramatically reshaped the world by the mid-1800s, the most profound transformation still lay ahead: a massive expansion of the technological frontier.

Technological Change

Major technological changes began to reshape the Western world, starting in the late 1700s and accelerating in the mid-1800s. The rise of global markets created demand that needed to be met, which led to the invention of new ways to serve that demand.

Broadly speaking, five significant technological changes supercharged global trade and capitalism.

Energy

Perhaps the most important of these technological innovations was the steam engine. While the use of steam as a source of energy had been known for centuries, it was not turned into a practical device until the late 1600s. It was James Watt’s design, developed between 1765 and 1776, that led to the creation of the modern steam engine. This is widely considered the spark that ignited the Industrial Revolution.

Energy, at a more philosophical level, is all there is. Much of social and economic existence is about energy transfer from one form to another. The steam engine transformed that transfer. It no longer required the kind of human energy that had powered centuries of labor, from building pyramids to weaving cloth.

But the steam engine was only the first step. By the 1870s, with the invention of the dynamo, which could provide smooth and continuous electric power, inventors like Edison and Tesla were actively experimenting with electricity.

Rapid improvements in generating, transmitting, and distributing electric power allowed for broader applications across the economy. Electricity began to be widely produced for industrial use.

Production

Given this new source of energy, new devices were created such as the power loom, the spinning jenny, and the cotton gin. These innovations drastically improved the productivity of the textile industry and reduced the labor needed per unit of output. This technological change dramatically reduced the cost of goods. Combined with growing markets, both domestic and global, it led to greater demand for both textiles and the raw materials needed to produce them, such as cotton.

In addition to the mechanization of production in sectors like textiles, another major innovation was the invention of the Bessemer Process for steel production. This allowed steel to be produced much more inexpensively. Before this process, steel was rare and mostly crafted by skilled artisans. With the Bessemer Process, it could now be produced cheaply and at scale.

I would add a third aspect of production technology. A few years ago, I read Simon Winchester’s The Perfectionists, which traces the rise of precision engineering. By the mid-1800s, the needs of manufacturing—repairability, scale, and precision—led to the creation of machine tools as well as precision, interchangeable parts.

Transportation

Now that you have supply and demand, you need to get them to meet. These technological innovations: steam, steel, and mechanization also enabled a rapid increase in transportation technologies. Railroads allowed countries to integrate their national markets, creating industries that could transport goods efficiently and enabling production to be located wherever it was most efficient, then supplied to wherever it was needed. Steamships played a similar role for domestic trade across rivers, and by the late 1800s, significant transoceanic trade had emerged, moving large volumes of people and goods across continents.

In 1876, the internal combustion engine was patented and later commercialized by the late 1880s. This led to the eventual rise of automobiles (including trucks) and road systems, that could move goods and people to places even railroads could not reach.

Information and Communication

The rise of the capitalist enterprise also led to the creation of a new type of good: information. Like physical goods, this information needed to travel. A series of important innovations made that possible. The telegraph, invented in the 1830s and commercialized in 1844, allowed for real-time communication over long distances. This was crucial for real-time pricing of goods, the trading of equities and commodities, and the centralized coordination of complex and sprawling enterprises distributed not only across the country but around the world. The telephone, patented in 1876, made communication even easier, though it was primarily a one-to-one technology.

Radio transformed communication once again. It enabled one-to-many communication, allowing politicians to reach their constituents, businesses to advertise and grow demand, and the creation of national markets for both attention and culture.

During this period, businesses expanded, which required more systematic recordkeeping. It was no longer enough to jot notes in ledgers or rely on unclear handwriting. The invention of the typewriter in the 1870s led to the production of even more information, which now needed to be sorted, sifted, and analyzed—and mailed through the growing postal service.

Organization and Management

Finally, beyond energy, production machines, transportation, and communication technologies, these ever-growing enterprises needed to manage their affairs more rigorously and efficiently as competition intensified. While significant changes to management and organizational practices occurred during this period, perhaps the most influential was Taylorism. This approach allowed for the systematization of work on the factory floor by breaking tasks down into small, incremental components and then reassembling them in the most efficient way possible.

Taylorism had the effect of de-skilling labor, but it also dramatically increased the demand for low-skilled workers who could “plug in” to modern factory systems.

Taylorism, combined with more rigorous statistical process control as well as advances in accounting, led to the rise of larger, more efficient organizations that could scale to sizes that would have been unimaginable just a few decades earlier. For instance, by 1929, just before the Great Depression, Ford had 174,126 employees, according to official records. By comparison, the estimated size of the Continental Army under George Washington that helped the US gain independence was a mere 80,000.

In less than 150 years, the power of the factory floor rivaled the power of armies. Atop these armies of workers was a new class of men made in the shuffle: Vanderbilt (Railroads), Carnegie (Steel), Rockafeller (Oil), Ford (Automobiles), Stanford (Railroads), and Morgan (Money). They not only held vast economic power but political, cultural, and social power as well.

How Trade * Tech Changed The World

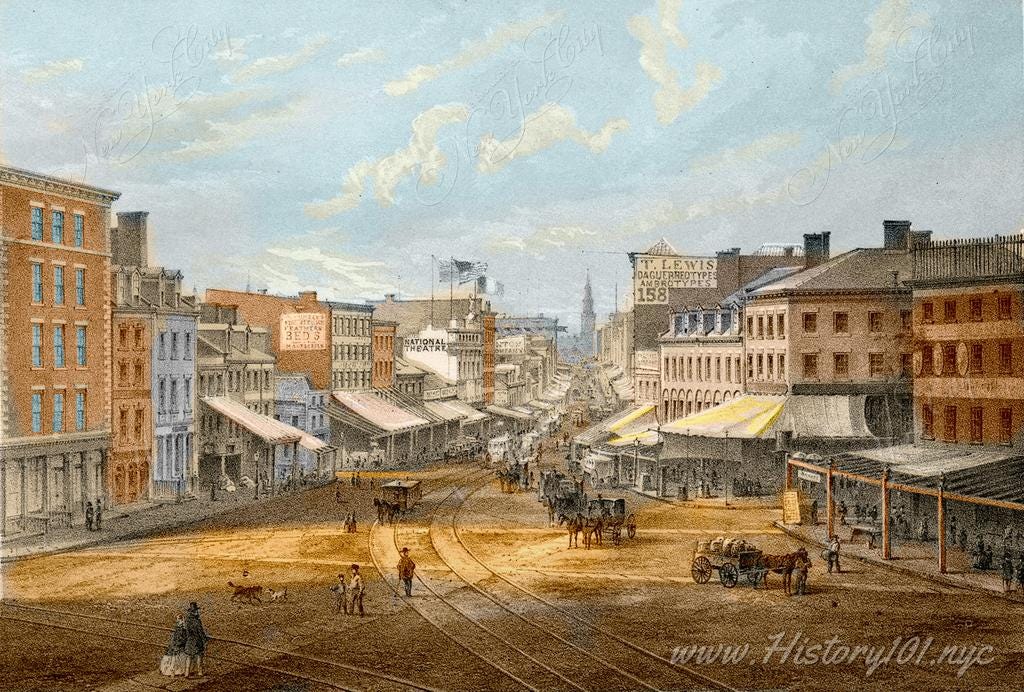

In 1875, most people lived in rural areas and worked in agriculture or small-scale trades. The economy was local, labor was manual and seasonal, and social life was organized around community and family. Businesses were small. Government had a limited role in economic life. Inequality existed but was less extreme. Social roles were more fixed, and there was less mobility.

By 1925, the world was different. Industrialization had reallocated people into cities and into factories. Large corporations replaced small businesses. Railroads, telegraphs, and typewriters created a faster and more connected and information rich economy. Immigration surged due to the demand for labor. Inequality widened, and in turn labor organized. The structure of everyday life looked very different. The assumptions people had about the social order no longer held.

Perhaps most importantly, once people rose to prominence in this new world, they did everything they could to calcify the structure they now controlled. This stark new order became the dominant social structure, replacing first feudal society, and later the simpler early bourgeois society of Marx.

Like all social structures before it, this new structure was hardened into place, self-became reinforcing, and functioned to preserve the advantages of those already at the top.

Many scholars began to ask: What the **** just hit us?

The Rise of Structural Sociology

The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. This is its task and its promise. - C. Wright Mills

The sociological imagination that emerged from this great transformation was a bit more systematic. It came in two flavors: one descriptive, one causal.

On the descriptive side, scholars began asking: What is this new world? What are its core parts? How are they connected?

On the causal side, the questions were harder to answer. How did this society come to be what it is now? Why does it work the way it does? And who benefits from the way things are set up? To answer these questions,

They studied institutions, roles, and hierarchies to understand why some groups had more power than others. They examined how bureaucracies shaped work and how organizations dominated social life. They asked how identity was formed and whether people had real agency inside tightly structured systems. And they explored how elites maintained power, how inequality was reproduced, and what caused institutions to hold—or break.

What Structural Sociology Teaches Us

The most powerful idea in structural sociology, at least to me, is that power flows through position.

One way that happens is through formal structure. Max Weber saw this in the rise of bureaucracy. In modern systems, what matters is not who you are, but where you are positioned. Authority is tied to role, not personality. Decisions follow the structure, not the individual (Economy and Society, 1922). Talcott Parsons made a similar point at a broader level. Institutions are held together by roles and rules. They don’t ask much of people beyond showing up and playing their part (The Social System, 1951).

Position is also built into how economies sort people. Peter Blau and Otis Dudley Duncan showed that outcomes are shaped by origin. Education, family, and class background all matter more than effort (The American Occupational Structure, 1967). Davis and Moore argued that inequality helps match talent to roles (Some Principles of Stratification, American Sociological Review, 1945), but the data told a different story. The system wasn’t meritocratic. It was structured to keep people where they started.

Bourdieu added that taste, language, and style all reflect early advantage. People raised in elite environments learn how to move through elite spaces (Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, 1979). That comfort, the ease of knowing how the game is played, is its own kind of power.

And once positions are locked in, they often reproduce themselves. C. Wright Mills described how elites move between institutions with little friction. The game is set up for them (The Power Elite, 1956). Antonio Gramsci explained how this kind of power is maintained not just through force, but through consent. People learn to see the structure as natural (Prison Notebooks, between 1929–1935). That’s when power is at its strongest: when it doesn’t have to explain itself.

These ideas and scholars were just the tip of the iceberg, and structural thought was never confined to explaining modern industrial society. It animated anthropology: Claude Lévi-Strauss studied pre-modern kinship systems, M.N. Srinivas analyzed the caste structure and social change in India, and others like S.F. Nadel and Bronisław Malinowski extended structural ideas into diverse cultural settings. Later, structural thinkers like Robert Merton introduced concepts such as role strain, while Harrison White and his students developed tools for mapping social structures as patterns of relations.

Over time, these structural tools became so deeply embedded in sociological thinking, and so analytically powerful (Google PageRank itself has origins in structural ideas), that it almost didn’t matter what they were used to study. The tools became the focus. In some ways, we became more interested in the architecture of structure itself than in the social world it was originally meant to describe and explain.

While the structuralism of early- to mid-20th-century sociology was slowly vanishing from mainstream sociological practice, it began to reappear in an unlikely place: economics. A new generation of economists began to notice that the postwar social structure of America looked eerily like the world the structural sociologists had once set out to describe.

The Rise of 21st Century Structural Sociology (in Economics)

In today’s economy, power is concentrated once again, and invisible social structures appear to matter more than ever. A modern cadre of social scientist have given us a mirror to look at our society.

Thomas Philippon has shown that market concentration has risen sharply since the 1990s. Fewer firms control more industries, and barriers to entry are higher than they appear (The Great Reversal, 2019).

José Azar, Martin Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu have shown that even firms that appear to compete are often owned by the same institutional investors. What looks like a market often turns out to be a set of interlocking positions. Power follows ownership and capital structure, not innovation or merit.

Position still sorts people, and it is harder to move than it used to be. Raj Chetty and his collaborators have shown that intergenerational mobility in the United States has declined sharply. For most people born into the bottom half of the income distribution, the odds of moving up are now lower than at any point in the postwar period (The Fading American Dream, 2017). Where you start matters more than how hard you work.

Wealth and income are no longer just outcomes. They function as mechanisms for reproducing advantage. Economists like Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez have shown that the top 1 percent has captured a growing share of wealth and income since the 1980s (Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 2013; Income Inequality in the United States, 2003). The structure reinforces itself: r > g.

Once these positions are established, they are hard to dislodge. Jacob Hacker (a political scientist) has shown how small shifts in policy and enforcement create lasting advantages for those already on top (Winner-Take-All Politics, 2010). Zoning laws, tax policy, school district boundaries, and corporate governance rules work together to maintain existing hierarchies. In fact, I have a paper with my co-author, Anuj Kumar, on how ostensibly freely accessible school ratings favor those who already have economic power: Who Captures the Value from Organizational Ratings?: Evidence from Public Schools (in Strategy Science).

These are not isolated problems, but rather structures that define the modern economy. They shape who gets ahead, who stays in place, and who is locked out from the start.

I want to think that the world we live in, the world our children will live in, is different from Gatsby’s. But, the re-emergence of structural sociology in modern economics may suggest otherwise.

Social science remains a worthy calling. We must again recommit to the hard work of asking: What the **** just hit us?

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

"Google PageRank itself has origins in structural ideas". Intellectually, the origins are older, e.g., finding the shadow price (principal eigenvector) of an input-output matrix in the context of centralized planning. See for example https://www.jstor.org/stable/24772?seq=1

Fascinating read, Sharique - you cover a LOT of ground here.