Hunting for Talent in Exponential Haystacks

How Technology Reshaped Recruiting—for Better or Worse—And Why Getting a Job Has Mostly Stayed the Same

Getting a job has never been easy, but today’s job market feels especially frustrating. Why is it so hard to get a foot in the door?

Workers: Why is it so hard to find a job?

A few weeks ago, the Wall Street Journal article “Ghost Jobs: Why Fake Jobs Are Proliferating” struck a nerve online.

It highlighted the growing frustration of job seekers who apply to countless listings, only to find that nearly one in five are 'ghost jobs'—roles posted with no intention of being filled. Ostensibly, companies use these postings to signal growth or hedge for exceptional candidates. If you're job hunting, that’s a pretty crappy feeling to hear that you were wasting your time on fake jobs.

But job hunting has never been a walk in the park. Even before ghost jobs, the odds were grim. A study by Farber et al. (2016) found that only 10% of job applications even receive a callback, and the numbers were worse for early career candidates, especially those with interim jobs (e.g., graduating with a CS degree but working at Target).

And even after landing an interview, the odds remain tough: recent numbers suggest an interview-to-hire rate of just 10-11%. If you want a 90% chance of getting at least one job offer, you’d need to apply to 230 positions. And if the callback and offer rates drop to just 5%? You’re looking at 920 applications. Four times as many!1 Clearly, your incentive is to apply to as many jobs as possible.

Firms: Why is it so hard to find good people to hire?

These odds have led to record numbers of job seekers applying to as many jobs as possible. But companies are on the other end of the “submit” button.

Firms now face a new problem: they’re drowning in applications; how do you find that proverbial needle in the haystack?

A few years ago, a friend was tasked with building a data science team at a major tech company. He followed the standard playbook: He posted a job and sent top candidates to HR, only to hear: 'Better teams already recruited them.' Searching PhD programs? 'Already in the system.' Expanding to lesser-known schools? Same result.

Finally, he went deeper, combing through conference papers to find “hidden gems” with cutting-edge research. When he sent the list to HR? They were already being recruited by someone else.

But what about the other side of the equation: the thousands of people who applied to those jobs and never heard back?

Information Problems in the Labor Market

The problem isn’t just about too many applications or too few hires. At its core, hiring is riddled with information gaps: two big ones, in particular.

For workers: What jobs are available? Is this a good fit? Will I enjoy working there? Even with job boards, LinkedIn, and employer branding, crucial details like pay, daily responsibilities, workplace culture, and long-term career growth often remain unclear.

The challenge for firms is just as complex: Who is out there, and how do we find them? Can they do the job, or will they struggle once hired? Will they stay long enough to justify the investment in training? Despite resumes, interviews, and assessments, firms still face uncertainty: How well a candidate will integrate into the company, collaborate with the team, and grow into future roles remains a gamble.

These are perennial problems, and over time, we've found ways to navigate them—first through networks and personal connections and later through a relentless cycle of technological innovation. This is a hiring arms race in which each new solution introduces fresh challenges.

Networking your way to your next job?

In 1973, Mark Granovetter, a sociologist now at Stanford University, published groundbreaking research on how Boston workers found their jobs. His seminal article, The Strength of Weak Ties (perhaps one of the most beautiful pieces of social science ever written), and his dissertation, Getting a Job, revealed a surprising fact: when it comes to finding jobs, weak ties—acquaintances, former colleagues, and distant contacts—matter more than close friends or family. Why? Strong ties tend to operate in the same social and professional circles, meaning they hear about the same opportunities. Weak ties bridge gaps between disconnected networks, exposing job seekers to new information and firms to new talent.

The transmission of labor market information through networks isn’t just to a worker’s advantage; it’s equally critical for firms. Just as workers struggle to see all possible job openings, firms struggle to see all possible candidates. Hiring through close networks limits access to fresh talent. Weak ties expand the search, helping firms identify candidates they might otherwise miss.

Social networks also convey information that doesn’t flow as easily through weak ties. Research by scholars such as Roberto Fernandez, Isabel Fernandez-Mateo, and Emilio Castilla—as well as many scholars in economics and business research—have highlighted the role of employee referrals in the hiring process. From the firm’s perspective, referrals offer insight into whether a candidate can be trusted and how well they might fit with the team. For workers, it’s about understanding whether the company is a good place to work and whether the manager is someone they can rely on. The real information that won’t be posted online comes from people, especially those you trust, such as those with whom you have strong ties.

Networks are potent tools for workers and firms but come with trade-offs. Information flows imperfectly through networks, and because of how we connect, strong biases determine who is “in” on the information and who is “out.” Though networks provide opportunities for some, they also restrict opportunities for others.

While referrals are an imperfect mechanism for connecting workers and firms, they have consistently accounted for approximately 35% of all hiring in both within-firm analyses and studies of specific samples going back to the 1970s.

However, technological change is unrelenting, and the Internet has transformed the job search process by scaling access to information— a role that informal networks have played for decades.

How Job Boards Led to Information Overload For Firms

If referrals were the dominant hiring mechanism of the pre-digital era, the Internet and job boards introduced a new paradigm: one in which information about job opportunities would flow freely, job markets would become more open, and hiring frictions would—poof—disappear.

But technology's impact is never so obvious. David Autor’s Wiring the Labor Market (2001) predicted these tensions.

He begins with a simple idea: At its core, the labor market is riddled with friction. It’s hard for workers and firms to find each other. When that process breaks down, the consequences ripple outward—bad matches, prolonged unemployment, and lost productivity. The naive Econ 101 solution? More information.

Then came the flood.

A quote from Autor (2001) summarizes this nicely.

“A natural consequence of lowering the cost of application is that many workers will apply for many more jobs. In fact, excess application appears to be the norm for on-line job postings, with employers reporting that they frequently receive unmanageable numbers of resumes from both under- and overqualified candidates, often repeatedly, and frequently from remote parts of the world.”

Jobs once drew dozens of applicants; now they get thousands.

The challenge flipped: instead of struggling to find enough candidates, firms were drowning in them. Drinking from a firehose doesn’t quite capture it.

Instead of carefully searching for candidates, they were inundated with applications—most of which were irrelevant. Their new challenge was to filter, rank, and sort the haystack.

Meanwhile, workers faced a different frustration: sending application after application, only to have them disappear into a void.

Networks had once been the gatekeepers to jobs. Online job boards were supposed to democratize hiring, but instead of removing bottlenecks, they relocated them. The fundamental challenge of hiring, matching the right worker with the right firm, was not solved. It had simply shifted from information access to sorting.

Hunting For Talent in Exponential Haystacks

The Rise of Outbound Recruiting

How could firms cut through the noise? Instead of waiting for the right candidates to apply, firms began hunting for talent (HfT).

LinkedIn, founded in 2003, gave firms access to millions of professionals—both job seekers and those who weren’t looking. As the platform scaled to hundreds of millions of users, hiring shifted from a passive process to a proactive search.

A few years ago, my collaborators Ines Black, Rembrand Koning, and I set out to answer a crucial question: How has this new information reshaped how firms find talent? Our findings, published in “Hunting for Talent: Firm-Driven Labor Market Search in the United States,” revealed a fundamental change in how hiring works today.

Historically, headhunting was a niche and costly practice in the American labor market. It required maintaining extensive candidate lists, conducting personalized outreach, and investing significant time in relationship-building. Outbound recruiting was both costly and uncommon and reserved mostly for senior hires. In 1991, only 4.9% of U.S. hires came through this method.

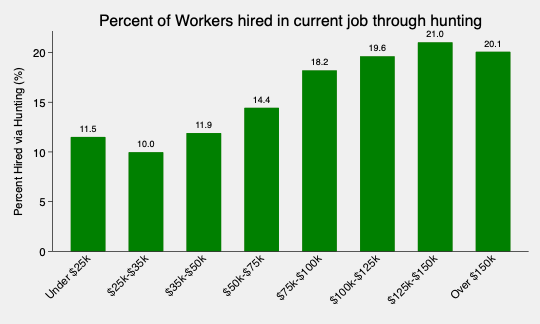

By 2022, the rate of outbound recruiting had tripled to 14.3% of all hires. Among those making 100k or more, that number was 4X the level of a few decades ago - close to 20%.2 Higher-paid and higher-skilled workers were those most affected by this shift (the LinkedIn set). This also wasn’t just a tech industry phenomenon. It was happening across sectors.

We observed firms adapting to this new flow of information, and their hiring data reflected the shift. Between 2010 and 2020, the share of firms hiring HR employees with recruiting skills rose from 33% to nearly 50%, signaling a growing emphasis on proactive talent acquisition. Demand spiked for recruiters skilled in scouring LinkedIn, GitHub, and other platforms for talent. Rather than sorting through endless applications, firms were building the capability to hunt for candidates directly.

As social scientists, we also worry about substitution. What practice was HfT displacing?

Surprisingly, outbound recruiting didn’t diminish referrals. We found that referrals still accounted for 33% of hires, unchanged since the 1970s and mostly constant across income levels. Networks kept doing what they were doing. Getting a Job was the same as it always was.

Instead, hunting for talent was replacing application-driven hiring. Hiring shifted from applications to search. The bottleneck moved from information access to sorting to search. Today, nearly 60% of workers earning $150K or more land jobs through referrals3, recruitment, or placement agencies. For them, direct applications to companies now make up only a minority of hires (~40%).

For a fair chance, workers struggling to stand out must signal their quality to recruiters and algorithms. Can AI bridge these gaps, or will it simply create new ones?

Can AI help firms filter and sort applicants and potential workers?

AI might create new information problems on both sides of the market. A few recent studies have given us a glimpse of how AI might affect firm decision-making.

Work by Li, Raymond, and Bergman (2020) showed that because AI is trained on past decisions, it leans heavily toward the candidates that firms have always hired. It scales up biases as it scales up efficiency. Their study puts this into sharp relief: standard supervised learning algorithms cut Black and Hispanic interviewees from 10% to 3-5% while boosting hiring yields. A contextual bandit model, which explicitly values exploration, significantly increased minority representation while still improving hiring rates. In short, algorithms don’t just reflect hiring practices; they can reshape them. Sometimes reinforcing bias, sometimes counteracting it.

Another creative study in this space, Cowgill (2020), shows that AI can improve hiring by selecting stronger candidates. However, its impact depends on the structure of human decision-making. When human evaluations are noisy and inconsistent, AI helps correct biases, leading to better interview performance, higher offer acceptance rates, and greater productivity, especially for non-traditional candidates. However, if human biases are rigid and systematically applied, AI is more likely to reinforce those patterns rather than counteract them.

AI doesn’t just mirror hiring practices. It can reshape them. As Li, Raymond, and Bergman (2020) and Cowgill (2020) show: when trained on past decisions, AI can scale biases, but models that encourage exploration can counteract this. AI’s impact also depends on whether human decision-making (its training data) is inconsistent (allowing AI to correct biases) or systematically biased (causing AI to reinforce them).

How will the rise of AI-based tools on the worker side affect screening?

While firms use AI to screen candidates, workers may use it for a range of labor market activities, especially to improve their resumes, cover letters, and essays.

Cowgill et al. (2024) find that generative AI, like ChatGPT, makes it harder for employers to distinguish strong candidates from weak ones, reducing screening accuracy by an average of 4–9%. Because AI flattens differences in applicant signals, evaluators will increasingly seek alternative ways to assess talent, such as background checks, direct interviews, and especially referrals.

What’s interesting is that while generative AI may make an undesirable candidate look slightly better, it can also help a potential star—especially one with non-native English fluency—better communicate their value. The key takeaway for me from these papers is that predicting AI’s impact is far from straightforward.

But here’s my prediction anyway: As AI slashes the cost of applying, even eliminating the effort of customizing a cover letter, job applications will flood in, looking sharper than ever.

Workers’ AI agents will flood companies with applications. Firms’ AI agents will ghost them.

Frankly, we should leave the agents to hunt for talent in the exponential haystack.

Real hiring, however, will continue much as before, leaning even more on harder-to-fake signals: who you know, what you’ve built, and the reputation of past employers. Instead of making hiring more data-driven, AI may paradoxically make networks matter more than ever. And in a world where AI can perfect every resume, the most valuable career advantage may remain what it’s always been: having the right people vouch for you.

The Best Algorithm? The Right People

This isn’t just an abstract discussion for me. I’ve lived it.

When I graduated college in 2003, the dot-com bubble had just burst. The NASDAQ had collapsed by 78%, and hiring had frozen in tech and finance. Maybe I had been too focused on my classes, or maybe I had just assumed that something would work out after graduation. Whatever the reason, I missed the recruiting cycle. So, I did what everyone says you should do: I sent dozens of job applications. No response.

Then, a friend told me that Target was hiring. Desperate to do something, I was offered a ten-dollar-an-hour job unloading trucks at night, so I took it. The work was brutal, and I lasted only two weeks.

A week later, I met up with a friend from high school at our regular spot, Dunkin’ Donuts on Route 27 in South Brunswick, New Jersey. His former roommate was leaving a research assistant job at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York to go to law school. “If you want it, my friend can put in a referral for you.”

Two weeks later, I had a job at MSKCC.

Data entry and small research tasks weren't glamorous, but I was surrounded by researchers passionate about their craft. I was hooked.

That job led to grad school, and with strong recommendations, I got in. And just like that, I was out of the labor market again.

Looking back, I realize that formal hiring processes contributed little to my trajectory. No one sifted through my resume in an applicant tracking system, no recruiter found me through a keyword search, and no AI model ranked me as a top candidate. Like many others, I got my first real job through a weak tie.

I also made one accidental smart choice. I left Target off my resume. If I had put it on there, would future employers have placed me in a different category? Maybe.

That’s the messy reality of hiring: It’s not just about what you can do.

All this to say: Skip the exponential haystack, call a friend, and grab a coffee.

The number of applications needed, N, to have at least a probability P of getting a job is given by N = ln(1 - P) / ln(1 - (C * H)), where C is the callback rate (fraction of applications leading to an interview), H is the offer rate given a callback (fraction of callbacks leading to an offer), and ln is the natural logarithm. For example, if P = 0.99, C = 0.10, and H = 0.10, then N = ln(1 - 0.99) / ln(1 - 0.01) ≈ 459, meaning 459 applications are needed to have a 99% chance of receiving at least one job offer.

14-20% is the percentage of people hired through this method. Those that a head hunter approached within the last year: 51%. Your highest earning employees: 66%!

Another great new paper shows that Weak ties drive hiring on LinkedIn.